This excerpt from “The Underground Railroad” by William Still describes how slaves in Virginia required a written pass when traveling in the evening.

Of course, this made escape even more difficult for those who didn’t have a pass.

One successful fugitive arrived from Virginia to the Philadelphia station on the Underground Railroad. Charles Thompson had work delivering a Richmond newspaper, The Daily National American.

The newspaper printing office gave him a pass to show when challenged. This would have been useful in starting his escape from Richmond.

The Philadelphia railroad committee was in the habit of gathering as much evidence as they could about the tribulations of the South. William Still duly reproduced the pass in his book.

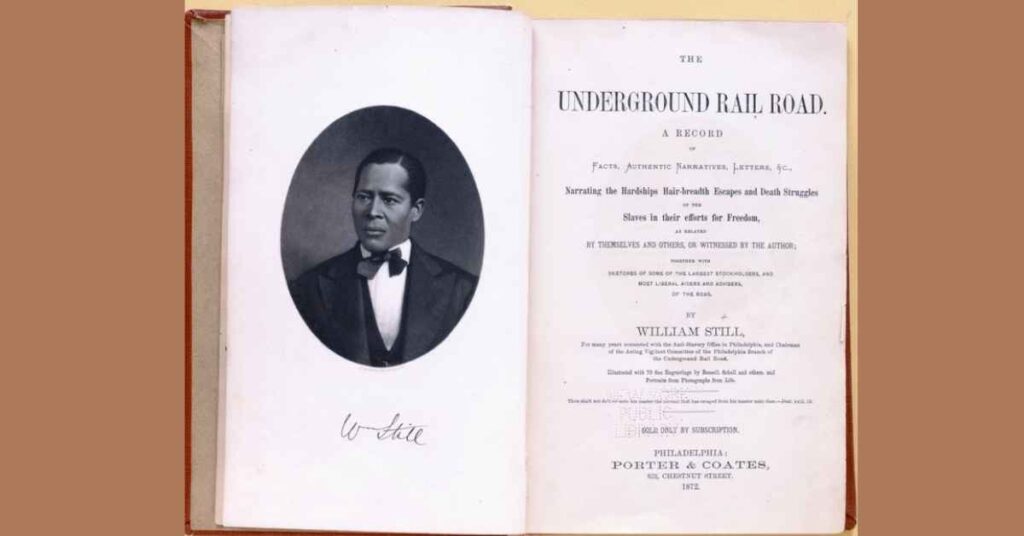

About The Book

“The Underground Railroad” was published in 1872. The book gives the testimonies of hundreds of slaves who escaped to freedom using the network of agents and safe houses.

The author, William Still, was a black abolitionist and businessman who was a key member of the Philadelphia stop in the freedom network.

The book is in the public domain. It can be found in the Library of Congress.

Any headings and italicized text in the excerpt below were added by the website editor. The rest is nearly verbatim from the book. There are some changes to the punctuation.

Excerpt – Charles Thompson’s Pass

The subjoined “pass” was brought to the Underground Rail Road station in Philadelphia by Charles.

And while it was interesting as throwing light upon his escape, it is important also as a specimen of the way the “pass” system was carried on in the dark days of Slavery in Virginia:

“NAT. AMERICAN OFFICE,

Richmond, July 20th, 1857.Permit Charles to pass and repass from this office to the residence of Rev B. Manly’s on Clay St., near 11th, at any hour of the night for one month.

WM. W. HARDWICK.”

[If you want to see another example of a travel pass, check out our excerpt on the escape from a tobacco factory.]

Commentary From William Still

[If you read much of William Still’s book, you will find that he often uses a wry sense of humor when describing this awful system of subjugation.]

It is a very short document, but it used to be very unsafe for a slave in Richmond, or any other Southern city, to be found out in the evening without a legal paper of this description.

The penalties for being found unprepared to face the police were fines, imprisonment and floggings.

The satisfaction it seemed always to afford these guardians of the city to find either males or females trespassing in this particular, was unmistakable. It gave them (the police) the opportunity to prove to those they served (slaveholders), that they were the right men in the right place, guarding their interests.

Then again they got the fine for pocket money, and likewise the still greater pleasure of administering the flogging.

Who would want an office, if no opportunity should turn up whereby proof could be adduced of adequate qualifications to meet emergencies?

But Charles was too wide awake to be caught without his pass day or night.

Consequently he hung on to it, even after starting on his voyage to Canada. He, however, willingly surrendered it to a member of the Committee at his special request.