This excerpt from “The Underground Railroad” documents the escape of Clarissa Davis from Portsmouth, Virginia.

Her first attempt to escape had partly failed and she was forced to hide from capture for over two months. But Clarissa was acquainted with a black steward on a steamboat. He agreed to help smuggle on board and conceal her if she could reach the vessel.

So, the inventive Clarissa disguised herself as a man and set off…

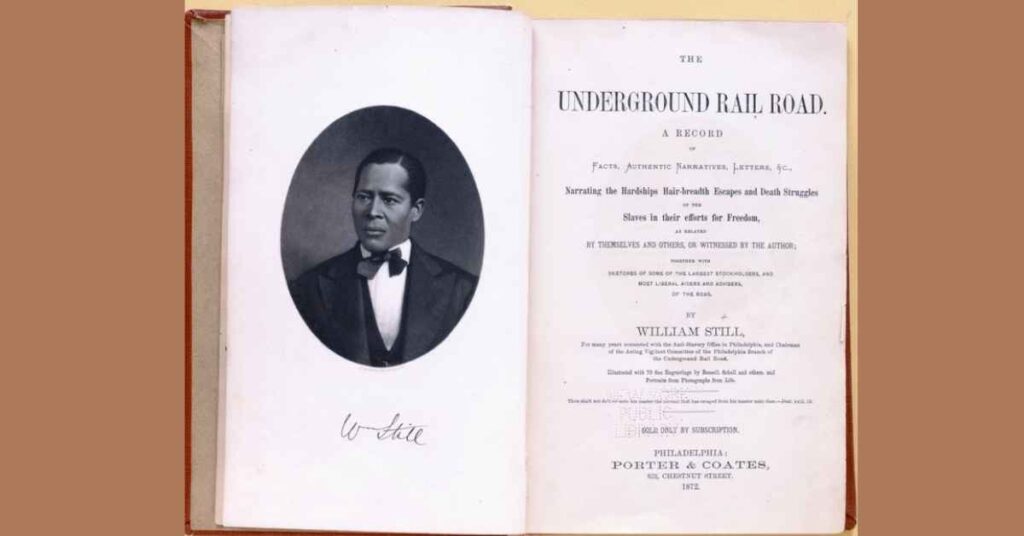

About The Book

“The Underground Railroad” was published in 1872. The book gives the testimonies of hundreds of slaves who escaped to freedom using the network of agents and safe houses.

The author, William Still, was a black abolitionist and businessman who was a key member of the Philadelphia stop in the freedom network.

The book is in the public domain. It can be found in the Library of Congress.

Excerpt – Arrived Dressed In Male Attire

[The headings and text in italics were added by the website editor. The rest is verbatim from the book]

Clarissa fled from Portsmouth, Va., in May, 1854, with two of her brothers.

Two months and a half before she succeeded in getting off, Clarissa had made a desperate effort, but failed. The brothers succeeded, but she was left.

She had not given up all hope of escape, however, and therefore sought “a safe hiding-place until an opportunity might offer,” by which she could follow her brothers on the U.G.R.R.

Clarissa was owned by Mrs. Brown and Mrs. Burkley, of Portsmouth, under whom she had always served. Of them she spoke favorably, saying that she “had not been used as hard as many others were.”

At this period, Clarissa was about twenty-two years of age, of a bright brown complexion, with handsome features, exceedingly respectful and modest, and possessed all the characteristics of a well-bred young lady.

For one so little acquainted with books as she was, the correctness of her speech was perfectly astonishing.

For Clarissa and her two brothers a “reward of one thousand dollars” was kept standing in the papers for a length of time, as these (articles) were considered very rare and valuable; the best that could be produced in Virginia.

Excerpt – Hiding For Seventy-Five Days

In the meanwhile the brothers had passed safely on to New Bedford, but Clarissa remained secluded, “waiting for the storm to subside.”

Keeping up courage day by day, for seventy-five days, with the fear of being detected and severely punished, and then sold, after all her hopes and struggles, required the faith of a martyr.

Time after time, when she hoped to succeed in making her escape, ill luck seemed to disappoint her, and nothing but intense suffering appeared to be in store.

Like many others, under the crushing weight of oppression, she thought she “should have to die” ere she tasted liberty.

Excerpt – Praying For Rain

In this state of mind, one day, word was conveyed to her that the steamship, City of Richmond, had arrived from Philadelphia, and that the steward on board (with whom she was acquainted), had consented to secrete her this trip, if she could manage to reach the ship safely, which was to start the next day.

This news to Clarissa was both cheering and painful. She had been “praying all the time while waiting,” but now she felt “that if it would only rain right hard the next morning about three o’clock, to drive the police officers off the street, then she could safely make her way to the boat.”

Therefore she prayed anxiously all that day that it would rain, “but no sign of rain appeared till towards midnight.”

The prospect looked horribly discouraging; but she prayed on, and at the appointed hour (three o’clock—before day), the rain descended in torrents.

Excerpt – Dressed In Male Attire

Dressed in male attire, Clarissa left the miserable coop where she had been almost without light or air for two and a half months, and unmolested, reached the boat safely, and was secreted in a box by Wm. Bagnal, a clever young man who sincerely sympathized with the slave, having a wife in slavery himself; and by him she was safely delivered into the hands of the Vigilance Committee.

Clarissa Davis here, by advice of the Committee, dropped her old name, and was straightway christened “Mary D. Armstead.”

Desiring to join her brothers and sister in New Bedford, she was duly furnished with her U.G.R.R. passport and directed thitherward.

Excerpt – Clarissa’s Father

Her father, who was left behind when she got off, soon after made his way on North, and joined his children.

He was too old and infirm probably to be worth anything, and had been allowed to go free, or to purchase himself for a mere nominal sum.

Slaveholders would, on some such occasions, show wonderful liberality in letting their old slaves go free, when they could work no more.

Aftermath

Clarissa reached her brothers and a sister in New Bedford. She wrote several letters of gratitude to the committee in Philadelphia who helped her passage.

One is reproduced in the book and is dated 26th August 1855. Amongst her expression of thanks, she mentions that her father’s health had improved, and he was able to work a little.