This is an excerpt from “The National Cyclopedia of The Colored Race” that was published in 1919.

The text is largely unchanged. I used additional punctuation and many more paragraph breaks for readability. I also added some subheadings.

Illustrations from the book are supplemented by our photos to add clarity and background.

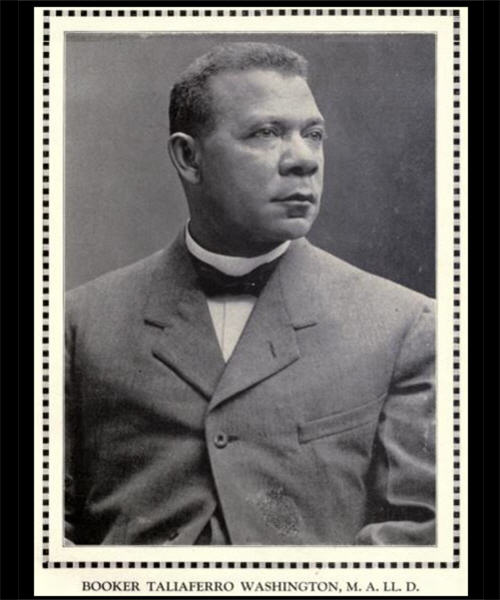

Booker T. Washington, a model of efficiency, was born a slave – but he lived to absorb so much of the white man’s civilization that he taught not only Negroes by a new method, but had his method adopted by white men as well.

Dr. Washington attended Hampton Institute, earning his way as he went. Indeed, all that Dr. Washington had as a start for his most remarkable career, was a determination to better himself and his people.

He lived to found and serve till it was fully established with no possible chance of failure, the largest institution for Negroes in the world – Tuskegee Institute.

This school has become a model for schools in all parts of the world.

Dr. Washington also founded the National Negro Business League, The International Race Congress, and was instrumental in the founding of the Southern Education Board.

He was honored by Harvard University with the degree of Master of Arts and was given the degree of LL. D. by Dartmouth.

In addition to these, he was given honorary degrees by a number of the leading Eastern and Southern Colleges. This was done as a recognition of his work.

A Student Of Books And Of Men

Dr. Washington never ceased to study, he studied at home, on the trains, on the long trips through the country.

He was as close a student of books as he was of men. His judgments of men and things are brought out clearly in the many books and periodicals of which he is the author.

Booker T. Washington who died at his home early Sunday morning, Nov. 14, 1915, was a big man out in the world; he was a bigger man at home among his teachers.

The world knew him for his eloquence, his homely wit, his tact, his shrewd diplomacy.

We knew him at home for his broad sympathies, for his kindness, his attention to little things, his infinite power of planning and working. His two last acts, one abroad and one at home, are strikingly significant of his balanced life.

His last act before the world was to make a journey to deliver an address.

His last act at home was to repair an old board fence which he had unwittingly ordered torn down.

At home or abroad he was never too big for even the humblest man to approach. Indeed, he had a sort of craze for bringing together the rude illiterate and the more cultivated members of his race.

He liked to assemble the rude black farmer, the schoolteacher, the lawyer, and the businessman.

He had a fondness for stopping the half illiterate preacher, for getting such in his office and looking into their minds.

An old-time mammy, or an old, old Negro farmer in his audiences seemed to inspire him more than the richest and most distinguished. He always rushed, as it were, into the arms of such at the closing of his big meetings.

Probably no single organization with which he ever had connection gave him quite the genuine satisfaction he got from the Annual Farmers’ Conference.

He delighted to banter these old fellows, to listen to their rude speeches and homely sayings. Many of his own stories and anecdotes sprang out of these meetings.

But he was no mere stag acquaintance. He welcomed all such to his fireside, to his office, his precious time, his helping hand, the mother protesting that her child did not make a class high enough, the student smarting under some misunderstanding with a teacher, the white banker or white farmer wishing to transact business – all had free access to him.

To be sure he kept a closed office, but this was to gain dispatch, not to exclude. It was no uncommon sight to find a vagrant Negro preacher, a distinguished visitor, a Negro farmer, a teacher or two, and a few students all waiting to see him.

Reports say that the doctors wondered how he lived so long. The more is the marvel when one thinks of the burdens he bore.

Washington’s Burdens

Having to raise thousands of dollars to provide food, heat, comfortable lodgings for 1500 students, he nevertheless kept his finger on the smallest details.

Now he was dictating a letter asking for funds, the next moment he would be summoning a workman or dictating a note about the weeds in a plot of ground, about a hedge, or a broken windowpane.

One moment he would be dictating a speech for some national occasion, the next he would be advising a means of disposing of “old Mollie,” one of the cows of the dairy herd, or “old Phil,” a lame mule.

So it was with the eggs and chickens from the poultry yard, the swede potatoes, the peaches, the corn, oats, pigs, the power plant, the lighting system, the way a new teacher was conducting a class in arithmetic or grammar.

And this thing he kept up from day to day, whether he was in New York or Alabama.

I myself have again and again, during the seven years in which I have had charge of the English work at Tuskegee Institute gotten notes making suggestions about a paragraph or a sentence in some student’s talk or commencement address.

Maximum Efficiency

There was only one way under the sun he could do this. He regulated his life to the very second. He husbanded time most miserly, though he was prodigal with his energies.

He had breakfasted and was out on horseback by 7:30 (he fancied the big iron gray pacer). His hour’s ride was in a sense recreative; in another sense, it was work.

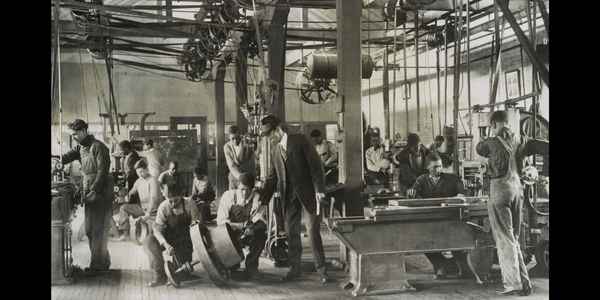

For he inspected the farm, the orchard, the shops, the school’s supplies, taking notes and giving direction.

If he rode out into the country, he usually returned with suggestions about a torn-off blind on a Negro church or the neglected garden of a Negro schoolhouse.

All the time he was stopping teachers and workmen by the way, giving them new tasks, requesting them to come to his office at a certain hour.

By half past eight he was in his office. For a certain time, he read and dictated letters.

In the meantime, the office boys were flying over the grounds and ringing the telephone bells, summoning Council members, the heads of departments, to a committee meeting, a meeting on the budget, on Commencement, on a new building, on the actions of a student or a teacher.

Up to the last second, he would keep his mind fixed on his reading or correspondence. He then took up the business in hand, dispensed with it, and went back to an article on teaching or on Negro homes or Negro business.

If he was slated to make a trip in a buggy or car, he kept his work until the clock was on the second. Then he stepped into the conveyance and was gone.

Woe unto him who brought a slow vehicle. Even so he would be at work. Between one stop and another on a speaking tour, he would sketch a half dozen plans – for articles, for grading a lawn, for remodelling a building, for rendering somebody a service.

Always and everywhere his plans inculcated this – to serve somebody, to make somebody happier. It might be by giving a body something; it was most often by giving one something to do.

This having things to hand, which to some minds, might appear at times extravagant was the very essence of his efficiency, as it is of any man’s efficiency.

The change of clothing was usually ready to hand. He had push bells and telephones in his office, and push bells and telephones in his study at home.

Efficiency About The Grounds

Wherever and whenever he went about the grounds an office boy, sometimes a stenographer, followed at his elbow to summon a workman or to take down a note on some weak point in workmanship.

His pet diversion was hunting. In the fall he would frequently steal an hour and run out to the woods.

To save time he kept a hunting outfit, gun cartridges, etc., at his home and one at the workplace of the young man who usually accompanied him, so that whenever the hunting time came he would not lose an hour in getting ready.

To some, this would be extravagance. To one whose time is precious, it is the highest economy.

With this practice of having things to hand, he coupled the habit of doing the thing then. His key word was “AT ONCE.”

Alas! how often Tuskegee teachers have seen that notice: Mr – will see the Principal “at once.”

The engagement might not last one third the time it required you to walk to the office ; but he attended to the thing there.

The errand boy gets the workman there. The stenographer took down the note on the spot. He went hunting then; he made his address then; he signed his letters then.

Each minute in the day seemed to have been for him an individual particle, to be dealt with and settled by the time the next one ticked around.

Pushed To The Extreme

For the last year or so he pushed this habit to the extreme, calling for teachers, workmen, council members, who were the advisory board, at midnight, at daybreak, at the meal hour.

Several times Mrs. Washington protested, seeking to restrain him. With the genius of premonition he would exclaim, “Let me alone. Let me do it now. I don’t know where I’ll be tomorrow.”

Some local joker tells this story which, though likely enough untrue, illustrates this habit of attending to one thing at the moment.

One afternoon in the fall while stealing his hour’s hunt he chanced to cross a part of the school’s farm in order to reach the woods. The name of the Director of the farming industries is Bridgeforth, that of the young man who went hunting with Dr. Washington, Foster.

Just as the Tuskegean and Foster entered the woods, a squirrel leaped from the ground and went scrambling up a tree.

Quick as a spark Dr. Washington levelled his gun. At the same moment, some thought about improving the farm evidently flashed across his mind.

Relaxing his gun the slightest bit, he turned to the young man and said: “Foster, get me Mr. Bridgeforth at once.”

Probably few Americans, white or black, have had a higher sense of duty than Booker T. Washington.

Tremendous Will

It mattered little who imposed the task or whether it was great or small, the thing was promised and must be done. Many of us here at Tuskegee feel that nothing but this sense of duty backed by a tremendous will, has kept him alive for the last few years.

A year or so ago we were holding our Annual Armstrong Memorial exercises. Dr. Washington had said that he would speak at this exercise, as he always did when he was at home.

Early in the afternoon of the appointed day he fell ill with a throbbing headache and his stomach in a turmoil. The doctor put him to bed and ordered him to remain there.

At eight o’clock that night he appeared and made his address, though he collapsed in the anteroom immediately afterwards.

Finally, just as he willed to do, to hold on, he could will to let go.

He was great in big things and in little things; great in the world and at home; but he was greatest in the assertion of his tremendous will.