This short biography is based on the autobiography of Dr. William James Edwards published in 1918.

William James Edwards was born in Snow Hill, Wilcox County, Alabama, in 1869. He would later build a renowned educational institution three-quarters of a mile from where he was born.

The Snow Hill Institute educated many generations of black students. It started as a one-room school in a log cabin and grew into a complex of twenty-seven buildings with an enrollment of four hundred students.

Early Days

William’s mother died before he turned one years of age. His grandmother looked after him while his father went away to work.

The baby William had originally been called Ulysses Grant Edwards, but his grandmother changed it to William. He added the name James to honour his preacher grandfather.

William’s grandmother sent him to school in the winter but often with only bread for his lunch. The other children teased him, but the young boy was determined to learn to read.

When his grandmother died, William’s father returned to take him and his sister to Selma. Despite his excitement at being in the big city, William fell seriously ill.

His aunt took him back to Snow Hill. While he was recuperating, he read voraciously and worked his way through a book of mathematics.

His aunt scrimped, saved, and begged for the money for medical treatment for William who could hardly walk from his illness. After four years, the teenager finally recovered his mobility in 1884.

Of course, this meant that he could work for the first time. Desperate to help his aunt and family, he picked fruit and cotton.

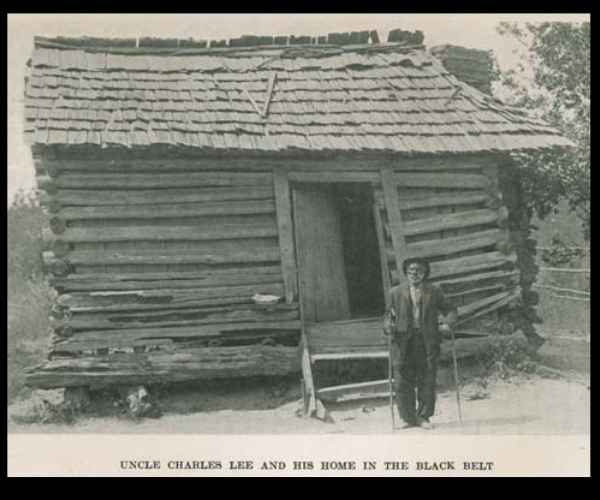

William, his aunt, and his young nephew lived in a one-room log cabin. This is an illustration from his autobiography of a typical cabin in the Black Belt region.

First Hearing About Tuskegee

In the summer of 1887, William was determined to go to church after seven years of absence.

But as he didn’t have proper clothes or shoes, his family went to a revival meeting without him. Undeterred, the youngster hid around the back of the church and listened through the cracks.

At the end of the sermon, the preacher spoke about the Tuskegee Institute. He explained how this school would take pupils without money who would work for their education.

When he told his elderly aunt that he wanted to attend Tuskegee, she greatly encouraged him.

Despite Tuskegee not having a fee, William knew he needed funds for shoes and clothing. He worked hard for a year to scrape together some savings.

Despite initial scepticism, his neighbors gave him nickels and dimes when they realized he was set on this course.

First Days At Tuskegee

William entered the Tuskegee Institute in 1869. His first days were so hard that he decided to leave.

But when he went to the school office, he met Booker T Washington. The great educator persuaded the youngster to stay.

William had several hurdles to overcome so that he could fit in. He had never used cutlery, but he carefully watched the other boys in the dining hall.

Another boy gave him a nightshirt, but he had no idea how to wear it. He waited until someone was getting ready for bed and watched what to do with the garment.

Work And Inspiration

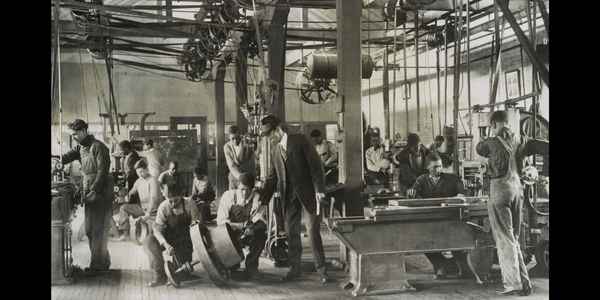

The Tuskegee Institute had different areas of work for students to try.

William tried the tin shop and the printing equipment but didn’t take to these fields. He found his home in the farming area.

In his autobiography, he doesn’t talk much about the education he received. But he is clear about the influence of Booker T Washington.

The one thing that made the deepest impression on me while at Tuskegee was Mr. Washington’s Sunday evening talks to the students.

He used to tell us that after getting our education we should return to our homes and there help the people. He said that the people were supporting Tuskegee in order that we might be able to help the masses of our people.

I could understand every word he said, and too, I felt always that he was talking directly to me.

These talks of Dr. Washington’s changed the course of my whole life.

Founding Snow Hill School And Industrial Institute

When he graduated from Tuskegee, William returned to his home ground where his beloved aunt still lived in old age.

He traveled around the region to get first-hand knowledge of the educational needs of the black communities.

He started his school in 1894 in an old log cabin with one teacher and three people.

One of his big challenges was that black parents who had spent all their lives at hard labour were hostile to their children’s education also involving industrial training.

During most of the year, their children had to work in the fields. They couldn’t see the purpose of having the children “work” in the school.

But Edwards insisted on keeping the industrial side of his school. The main focus was on agriculture as so many of the local community worked on the land.

Growing The School

After the first year, there was a clear demand for more teachers. But the school only had one log cabin!

To build another, Edwards worked the summer at a lumber yard. He struck a deal to take his pay in meals and enough lumber for build two more rooms.

The teachers in these first years had graduated from Tuskegee with Edwards.

An Old Ally

William Edwards was raised on the plantation where his grandmother and aunt had been enslaved.

The ladies remained on good terms with the plantation owner, Mr. R.O. Simpson, after emancipation. Simpson continued to take an interest in their family.

He also took an interest in the new industrial school and talked at length with William about the young man’s plans.

William was sorely in need of agricultural land to expand his school.

R.O. Simpson first gave seven acres. He then added another thirty-three. He would eventually give a further sixty acres.

Years later, the school bought half of his plantation to bring their land to nearly two thousand acres.

Campaigning For Funds

Edwards was adamant that his school would be non-denominational. In other words, it would not be associated specifically with one faith.

That meant that raising funds was more challenging.

Booker T Washington brought William on a tour to the Northern states to meet influential people who wanted to help black communities in the South.

Edwards spoke about Snow Hill at churches and meeting halls through the summer if 1898. He successfully raised funds for his institute.

Sadly, his enjoyment of this success was dampened by the death of his beloved aunt while he was in Boston.

William speaks in his book about how he was not very good at raising funds. But he managed to hit the mark on occasion.

He spoke in 1906 at the 25th anniversary of the Tuskegee Institute. Andrew Carnegie was in the audience, and he donated ten thousand dollars to Snow Hill. In today’s terms, that’s about 1.5 million dollars.

What Happened To The Snow Hill Institute?

When Dr Edwards retired in 1924, the State of Alabama took over the institute as a public school.

William Edwards was buried on the grounds of the school.

When Wilcox County schools were desegregated in the early 1970s, the school closed.

Descendants Of William James Edwards

Consuela Lee Moorehead was a granddaughter of Edwards. She attended the Snow Hill Institute.

Conseula, the daughter of musicians, was a talented jazz pianist and a music teacher. After the Snow Hill Institute was closed, Consuela reopened it in 1979 as a performing arts center.

William has many great-grandchildren who are talented artists. They include the film makers Spike Lee and Malcolm D. Lee.

Autobiography

William James Edwards publishes his autobiography in 1919. It is titled “Twenty-Five Years In The Black Belt”.

The text is available at the archives of the University of North Carolina.