This excerpt from “The Underground Railroad” documents the escape of Robert Brown who swam a horse across the Potomac River on the night of Christmas.

He made this desperate escape five days after his wife and children had been sold to another owner.

It’s a harrowing tale that brought Brown from Martinsburg, Virginia to the underground stop in Philadelphia.

Excerpt – Robert Brown, Underground Railroad

In very desperate straits many new inventions were sought after by deep-thinking and resolute slaves, determined to be free at any cost.

But it must here be admitted, that, in looking carefully over the more perilous methods resorted to, Robert Brown, alias Thomas Jones, stands second to none, with regard to deeds of bold daring.

This hero escaped from Martinsburg, Va., in 1856. He was a man of medium size, mulatto, about thirty-eight years of age, could read and write, and was naturally sharp-witted.

He had formerly been owned by Col. John F. Franie, whom Robert charged with various offences of a serious domestic character.

Furthermore, he also alleged, that his “mistress was cruel to all the slaves,” declaring that “they (the slaves), could not live with her,” that “she had to hire servants,” etc.

In order to effect his escape, Robert was obliged to swim the Potomac river on horseback, on Christmas night, while the cold, wind, storm, and darkness were indescribably dismal.

This daring bondman, rather than submit to his oppressor any longer, perilled his life as above stated.

Where he crossed the river was about a half a mile wide. Where could be found in history a more noble and daring struggle for Freedom?

The wife of his bosom and his four children, only five days before he fled, were sold to a trader in Richmond, Va., for no other offence than simply “because she had resisted” the lustful designs of her master, being “true to her own companion.”

After this poor slave mother and her children were cast into prison for sale, the husband and some of his friends tried hard to find a purchaser in the neighborhood; but the malicious and brutal master refused to sell her—wishing to gratify his malice to the utmost, and to punish his victims all that lay in his power, he sent them to the place above named.

In this trying hour, the severed and bleeding heart of the husband resolved to escape at all hazards, taking with him a daguerreotype likeness of his wife which he happened to have on hand, and a lock of hair from her head, and from each of the children, as mementoes of his unbounded (though sundered) affection for them.

After crossing the river, his wet clothing freezing to him, he rode all night, a distance of about forty miles. In the morning he left his faithful horse tied to a fence, quite broken down.

He then commenced his dreary journey on foot—cold and hungry—in a strange place, where it was quite unsafe to make known his condition and wants. Thus for a day or two, without food or shelter, he traveled until his feet were literally worn out, and in this condition he arrived at Harrisburg, where he found friends.

Passing over many of the interesting incidents on the road, suffice it to say, he arrived safely in this city, on New Year’s night, 1857, about two hours before day break (the telegraph having announced his coming from Harrisburg), having been a week on the way.

The night he arrived was very cold; besides, the Underground train, that morning, was about three hours behind time; in waiting for it, entirely out in the cold, a member of the Vigilance Committee thought he was frosted. But when he came to listen to the story of the Fugitive’s sufferings, his mind changed.

Scarcely had Robert entered the house of one of the Committee, where he was kindly received, when he took from his pocket his wife’s likeness, speaking very touchingly while gazing upon it and showing it.

Subsequently, in speaking of his family, he showed the locks of hair referred to, which he had carefully rolled up in paper separately.

Unrolling them, he said, “this is my wife’s;” “this is from my oldest daughter, eleven years old;” “and this is from my next oldest;” “and this from the next,” “and this from my infant, only eight weeks old.”

These mementoes he cherished with the utmost care as the last remains of his affectionate family.

At the sight of these locks of hair so tenderly preserved, the member of the Committee could fully appreciate the resolution of the fugitive in plunging into the Potomac, on the back of a dumb beast, in order to flee from a place and people who had made such barbarous havoc in his household.

His wife, as represented by the likeness, was of fair complexion, prepossessing, and good looking—perhaps not over thirty-three years of age.

Source

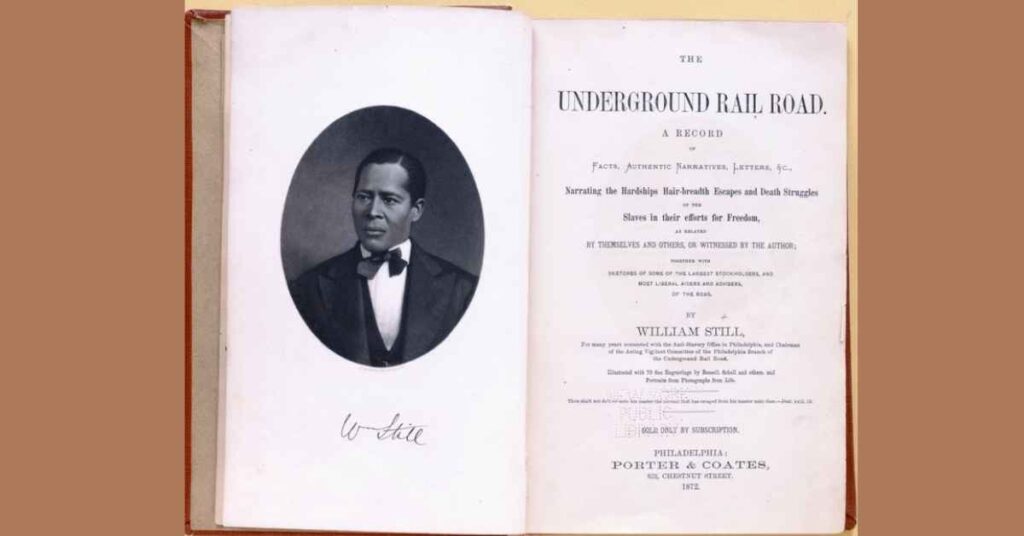

The Underground Railroad by William Still was published in 1872.

The book is in the public domain. It can be found in the Library of Congress.