Isaac “Ike” Reynolds was from Detroit, Michigan. a sophomore at Wayne State University, and also an activist with CORE (Congress Of Racial Equality) in 1961.

He got a call early one morning in May of 1961 to join the three-day bus ride from Sumter, South Carolina, to Birmingham, Alabama.

He flew from Detroit to Atlanta where he got a lift to Sumter.

Planned Actions

The plan was to put a mixed group of seven or eight Riders on several buses.

At least one black rider would sit in the front rows and refuse any request to move to the back of the bus. The others would spread around the bus, sitting in interracial pairs.

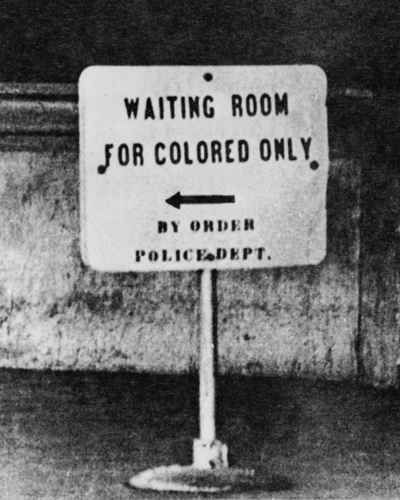

When they disembarked at bus stations, they would enter whites-only areas and restrooms. They would eat at white food counters and drink from white water fountains.

All the while, the riders were trained to act non-aggressively.

Early Stages Of The Journey

Ike Reynolds joined a group that traveled by bus from Sumter to New Orleans.

They had little trouble at stops in Mississippi when they sat at white counters and ordered food.

The worst reaction was negative remarks. At one food counter, the white manager ordered a black worker to serve the food.

Ike and the riders were even joined for dinner by Dr. Martin Luther King on one evening.

But the organizers and the riders knew that things would be different in Alabama. The night before the ride from Atlanta to Birmingham, they linked arms and sang “we shall overcome”.

Ike And The Trailways Group

The group then organized themselves into two staggered trips. One group traveled on a Greyhound bus and the other with Trailways.

The Greyhound group is perhaps better known in history. They were forced off their bus which was firebombed. The photos of the burning bus made the front pages around the world.

But the Trailways group had a similarly grim experience.

Ike Reynolds was with the Trailways Riders. When he and his companions were queuing for tickets, they noticed what seemed like regular white travelers in the line being approached by burly scowling men.

The regular travelers left the line and were replaced by the new white arrivals at the station. These turned out to be local klansmen.

Journalists On Board

Two representatives from Jet magazine were also on board the Trailways bus.

Simeon Booker was a renowned black journalist. He covered the 1955 murder of Emmett Till amongst other abuses against African Americans.

Ted Gaffney was a black freelance photographer hired by Jet to accompany Booker. Just by having a camera, he was a natural target. Yet he was keen to document whatever happened.

Attacked On the Trailways Bus

When the Trailways group disembarked at Anniston, they learned that the Greyhound bus with the other group had been set on fire.

Ike and the other Riders bravely got back on the bus.

The Klansmen launched a vicious attack during the trip while the driver continued the journey. Some of the Riders were beaten senseless.

This is what Booker wrote for Jet magazine:

For two hours, the bus roared toward Birmingham, its CORE passengers and Negroes terrorized, intimidated, afraid to even move.

Simeon Booker

When the bus arrived in Birmingham, the klansmen disembarked and disappeared into the gathered mob.

The bloodied Riders also disembarked to be met by a large number of KKK members.

The klansmen had the tacit support of the local police who had arranged to give them fifteen uninterrupted minutes to attack the freedom riders.

The photographer, Ted Gaffney, said:

They had these iron pipes around 18 inches long and started beating the Freedom Rider.

Ted Gaffney

Beaten By The Mob

Ike Reynolds was brutally attacked by a mob that left him semiconscious beside a trash bin.

A black man who was simply passing by and had nothing to do with the riders got caught up with Ike and was also beaten.

Some of the other riders suffered even worse physical damage. After the police decided enough time had passed, they told the klansmen to depart the area.

Ike and the local man were spotted by a CBS newsman sitting dazed and bleeding on the curb. When approached, they immediately agreed to be interviewed. The newsman took them back to his motel.

Ike was fortunate in this regard as the other riders had a lot of difficulty in securing a taxi to get away from the station. Thankfully, a black driver took them through back roads to the parsonage of a black church.

The newsman eventually brought Ike to join the other Riders at the parsonage. His friends fell upon him with relief that he had survived.

The following day was Sunday. The CBS radio network in particular had strong broadcasts with eyewitness accounts of the brutality of the KKK and the lack of protection from the police.

Getting Out Of Birmingham

Every bus driver in Birmingham refused to work on a bus with the freedom riders.

This left the group stuck in the city in increasing danger of mob rule.

Robert F. Kennedy, the Attorney General, sent through orders that ensured they were bundled onto a flight late that night.

What Ike Did Next

After the bombing of one bus and the mob beatings, many within the cause believed that the Freedom Rides shouldn’t continue.

Ike Reynolds was one of the most strident in arguing that there should be more freedom riders, not fewer.

He bravely led a new group on a Trailways bus from Montgomery to Jackson. Two more bus loads followed. All seventeen were jailed.

Freedom Riders On The Trailways Bus

These were the seven Freedom Riders on the Trailways Bus that stopped at Anniston:

- Walter Bergman, a retired white teacher and union activist from Michigan

- Frances Bergman, Walter’s 57-year-old wife and former schoolteacher

- Herman Harris, a black student at Morris College

- Jerry Moore, a black student at Morris College

- Jim Peck, a white union activist and journalist

- Charles Person, a black freshman at Morehouse College

- Ike Reynolds, subject of this article