This excerpt from “The Underground Railroad” by William Still documents the escape of Sam Nixon from Norfolk, Virginia, on a steamboat. This successful fugitive changed his name to Thomas Bayne.

Bayne was in bondage to a dentist and learned all about the profession. He didn’t just do the books, he did a third of the dental work on the patients.

When he arrived in Philadelphia, the local committee of the Underground Railroad urged him to continue to freedom in Canada. However, he was determined to settle in New Bedford.

There, he eventually set up a successful dental practice. Four years after arriving there, he was elected as a city councilor.

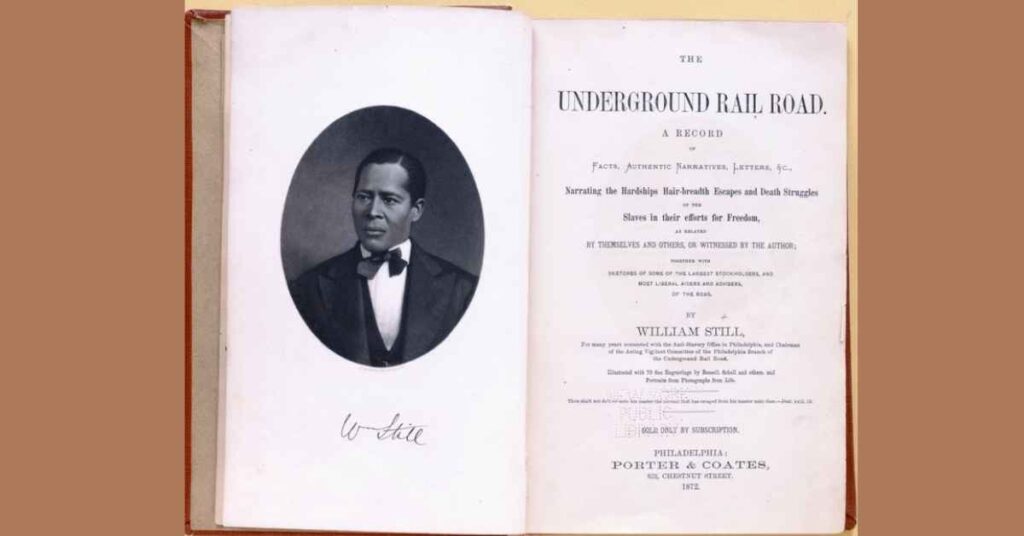

About The Book

“The Underground Railroad” was published in 1872. The book gives the testimonies of hundreds of slaves who escaped to freedom using the network of agents and safe houses.

The author, William Still, was a black abolitionist and businessman who was a key member of the Philadelphia stop in the freedom network.

The book is in the public domain. It can be found in the Library of Congress.

Any headings and italicized text in the excerpt below were added by the website editor. The rest is nearly verbatim from the book. There are some changes to the punctuation.

Excerpt – Sam Nixon Alias Dr. Thomas Bayne

Few could be found among the Underground Rail Road passengers who had a stronger repugnance to the unrequited labor system, or the recognized terms of “master and slave,” than Dr. Thomas Bayne.

Nor were many to be found who were more fearless and independent in uttering their sentiments.

His place of bondage was in the city of Norfolk, Va., where he was held to service by Dr. C.F. Martin, a dentist of some celebrity.

Learning Dentistry

While with Dr. Martin, “Sam” learned dentistry in all its branches, and was often required by his master, the doctor, to fulfil professional engagements, both at home and at a distance, when it did not suit his pleasure or convenience to appear in person.

In the mechanical department, especially, “Sam” was called upon to execute the most difficult tasks.

This was not the testimony of “Sam” alone; various individuals who were with him in Norfolk, but had moved to Philadelphia, and were living there at the time of his arrival, being invited to see this distinguished professional piece of property, gave evidence which fully corroborated his.

The master’s professional practice, according to “Sam’s” calculation, was worth $3,000 per annum. Full $1,000 of this amount in the opinion of “Sam” was the result of his own fettered hands.

Not only was “Sam” serviceable to the doctor in the mechanical and practical branches of his profession, but as a sort of ready reckoner and an apt penman, he was obviously considered by the doctor, a valuable “article.”

He would frequently have “Sam” at his books instead of a book-keeper.

Of course, “Sam” had never received, from Dr. M., an hour’s schooling in his life. But having perceptive faculties naturally very large, combined with much self-esteem, he could hardly help learning readily.

Had his master’s design to keep him in ignorance been ever so great, he would have found it a labor beyond his power.

Not Ill-Treated But Not Properly Paid

But there is no reason to suppose that Dr. Martin was opposed to Sam’s learning to read and write. We are pleased to note that no charges of ill-treatment are found recorded against Dr. M. in the narrative of “Sam.”

True, it appears that he had been sold several times in his younger days, and had consequently been made to feel keenly, the smarts of Slavery.

But nothing of this kind was charged against Dr. M., so that he may be set down as a pretty fair man, for aught that is known to the contrary, with the exception of depriving “Sam” of the just reward of his labor, which, according to St. James, is pronounced a “fraud.”

The doctor did not keep “Sam” so closely confined to dentistry and book-keeping that he had no time to attend occasionally to outside duties.

Working For The Underground Railroad

It appears that he was quite active and successful as an Underground Rail Road agent, and rendered important aid in various directions.

Indeed, Sam had good reason to suspect that the slave-holders were watching him, and that if he remained, he would most likely find himself in “hot water up to his eyes.”

Wisdom dictated that he should “pull up stakes” and depart while the way was open.

He knew the captains who were then in the habit of taking similar passengers, but he had some fears that they might not be able to pursue the business much longer.

In contemplating the change which he was about to make, “Sam” felt it necessary to keep his movements strictly private.

Concern For His Wife And Daughter

Not even was he at liberty to break his mind to his wife and child, fearing that it would do them no good, and might prove his utter failure.

His wife’s name was Edna and his daughter was called Elizabeth; both were slaves and owned by E.P. Tabb, Esq., a hardware merchant of Norfolk.

No mention is made on the books, of ill-treatment, in connection with his wife’s servitude; it may therefore be inferred, that her situation was not remarkably hard.

It must not be supposed that “Sam” was not truly attached to his wife. He gave abundant proof of true matrimonial devotion, notwithstanding the secrecy of his arrangements for flight.

Being naturally hopeful, he concluded that he could better succeed in securing his wife after obtaining freedom himself, than in undertaking the task beforehand.

Escape On A Schooner

The captain had two or three other Underground Rail Road male passengers to bring with him, besides “Sam,” for whom, arrangements had been previously made. No more could be brought that trip.

At the appointed time, the passengers were at the disposal of the captain of the schooner which was to bring them out of Slavery into freedom.

Fully aware of the dangerous consequences should he be detected, the captain, faithful to his promise, secreted them in the usual manner, and set sail northward.

Instead of landing his passengers in Philadelphia, as was his intention, for some reason or other (the schooner may have been disabled), he landed them on the New Jersey coast, not a great distance from Cape Island.

He directed them how to reach Philadelphia.

Sam knew of friends in the city, and straightway used his ready pen to make known the distress of himself and partners in tribulation.

In making their way in the direction of their destined haven, they reached Salem, New Jersey, where they were discovered to be strangers and fugitives, and were directed to Abigail Goodwin, a Quaker lady, an abolitionist, long noted for her devotion to the cause of freedom, and one of the most liberal and faithful friends of the Vigilance Committee of Philadelphia.

A Quaker’s Confusion

This friend’s opportunities of witnessing fresh arrivals had been rare, and perhaps she had never before come in contact with a “chattel” so smart as “Sam.”

Consequently she was much embarrassed when she heard his story, especially when he talked of his experience as a “Dentist.”

She was inclined to suspect that he was a “shrewd impostor” that needed “watching” instead of aiding.

But her humanity forbade a hasty decision on this point. She was soon persuaded to render him some assistance, notwithstanding her apprehensions.

While tarrying a day or two in Salem, “Sam’s” letter was received in Philadelphia. Friend Goodwin was written to in the meantime, by a member of the Committee, directly with a view of making inquires concerning the stray fugitives, and at the same time to inform her as to how they happened to be coming in the direction found by her.

Arriving In Philadelphia

In due time Samuel and his companions reached Philadelphia, where a cordial welcome awaited them.

The confusion and difficulties into which they had fallen, by having to travel an indirect route, were fully explained.

And to the hearty merriment of the Committee and strangers, the dilemma of their good Quaker friend Goodwin at Salem was alluded to.

After a sojourn of a day or two in Philadelphia, Samuel and his companions left for New Bedford.

Canada was named to them as the safest place for all Refugees; but it was in vain to attempt to convince “Sam” that Canada or any other place on this Continent, was quite equal to New Bedford.

His heart was there, and there he was resolved to go. And there he did go too, bearing with him his resolute mind, determined, if possible, to work his way up to an honorable position at his old trade, Dentistry, and that too for his own benefit.

Aided by the Committee, the journey was made safely to the desired haven, where many old friends from Norfolk were found.

Becoming Dr Thomas Bayne, City Councillor

Here our hero was known by the name of Dr. Thomas Bayne – he was no longer “Sam.”

In a short time the Dr. commenced his profession in an humble way.

While, at the same time, he deeply interested himself in his own improvement, as well as the improvement of others, especially those who had escaped from Slavery as he himself had.

Then, too, as colored men were voters and, therefore, eligible to office in New Bedford, the Doctor’s naturally ambitious and intelligent, turn of mind led him to take an interest in politics.

And before he was a citizen of New Bedford four years, he was duly elected a member of the City Council.

He was also an outspoken advocate of the cause of temperance, and was likewise a ready speaker at Anti-slavery meetings held by his race.

Aftermath

The above excerpt is the end of Thomas Bayne’s account in The Underground Railroad.

You may be wondering about his wife and daughter. We know that he was able to find his daughter in Norfolk and send her to Massachusetts.

When he died in 1888, he left his property to his daughter.