This excerpt from “The Underground Railroad” documents the escape of Charlotte Giles and Harriet Eglin by train from Baltimore, Maryland, to Philadelphia.

This escape is notable because escaping by train presented different difficulties when compared to by steamboat.

One of the challenges with the steamboat was embarking without being challenged. You can learn how women managed this in our excerpt on the escape of Susan Brooks. But once on board, a steward who was an agent of the Railroad would find a place to hide the passengers below deck.

Some fugitives traveled by train by hiding inside packing boxes as if they were goods. Our excerpt of Henry Box Brown’s escape illustrates this method.

But Charlotte and Harriet were even more ingenious. They brazenly and bravely posed as passengers while their furious master searched high and low through every car.

Personally, I think these girls should get some kind of posthumous acting award.

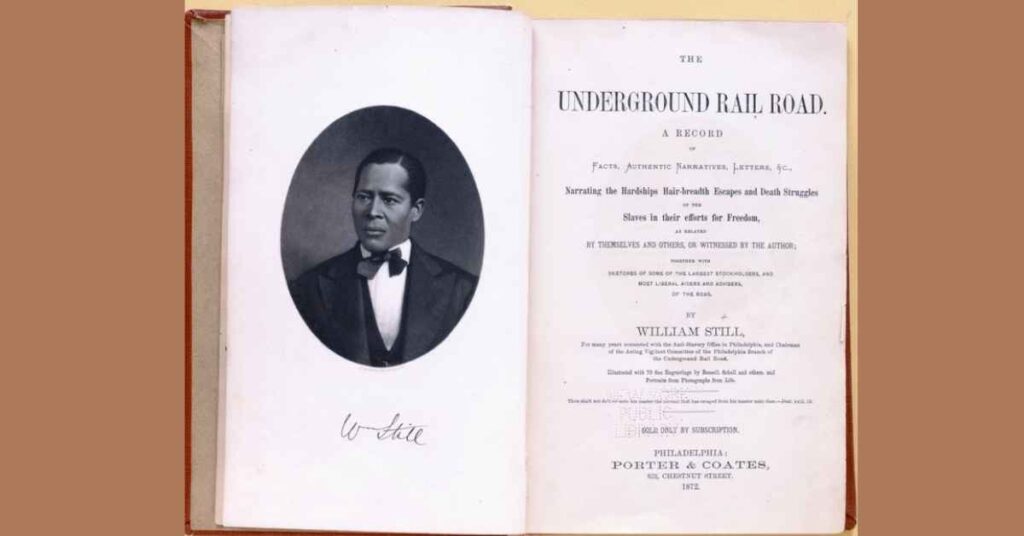

About The Book

“The Underground Railroad” was published in 1872. The book gives the testimonies of hundreds of slaves who escaped to freedom using the network of agents and safe houses.

The author, William Still, was a black abolitionist and businessman who was a key member of the Philadelphia stop in the freedom network.

The book is in the public domain. It can be found in the Library of Congress.

Excerpt – Escape Of Charlotte Giles And Harriet Eglin By Train

About the 31st of May, 1856, an exceedingly anxious state of feeling existed with the active Committee in Philadelphia.

In the course of twenty-four hours four arrivals had come to hand from different localities…

Party No. 1 consisted of Charlotte Giles and Harriet Eglin, owned by Capt. Wm. Applegarth and John Delahay.

Neither of these girls had any great complaint to make on the score of ill-treatment endured.

So they contrived each to get a suit of mourning, with heavy black veils, and thus dressed, apparently absorbed with grief, with a friend to pass them to the Baltimore depot (hard place to pass, except aided by an individual well known to the R.R. company), they took a direct course for Philadelphia.

The Master Enters The Train!

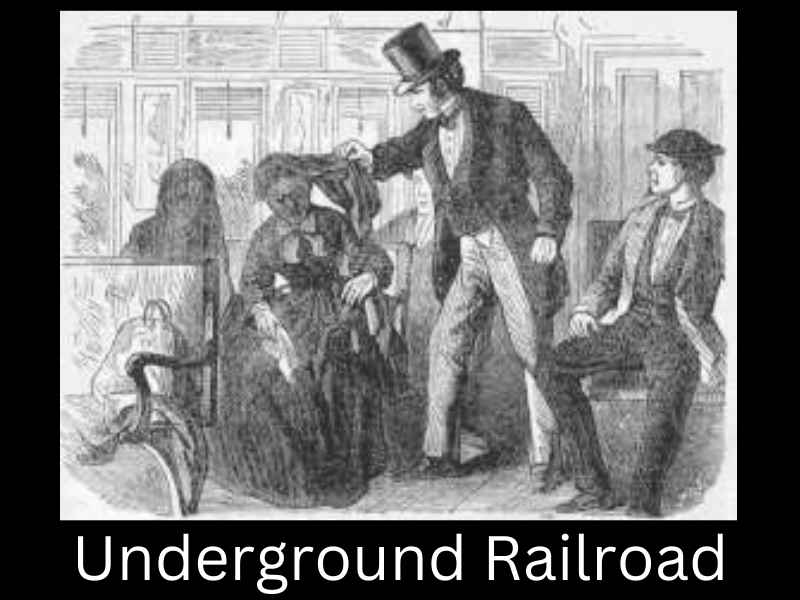

While seated in the car, before leaving Baltimore (where slaves and masters both belonged), who should enter but the master of one of the girls!

In a very excited manner, he hurriedly approached Charlotte and Harriet, who were apparently weeping.

Peeping under their veils, “What is your name,” exclaimed the excited gentleman. “Mary, sir,” sobbed Charlotte.

“What is your name?” (to the other mourner) “Lizzie, sir,” was the faint reply.

On rushed the excited gentleman as if moved by steam – through the cars, looking for his property; not finding it, he passed out of the cars, and to the delight of Charlotte and Harriet soon disappeared.

Fair business men would be likely to look at this conduct on the part of the two girls in the light of a “sharp practice.” In military parlance it might be regarded as excellent strategy.

Be this as it may, the Underground Rail Road passengers arrived safely at the Philadelphia station and were gladly received.

A brief stay in the city was thought prudent lest the hunters might be on the pursuit. They were, therefore, retained in safe quarters.

Warned By A Stranger

[ Eleven other fugitives had arrived at the offices of the Committee on the same day as the two girls. We have a separate excerpt on an equally audacious escape by horse and coach, which was followed by a transfer to the same train as the girls. This excerpt continues the narrative…]

It may be seen how great was the danger to which all concerned were exposed on account of the bold and open manner in which these parties had escaped from the land of the peculiar institution.

Notwithstanding, a feeling of very great gratification existed in view of the success attending the new and adventurous modes of traveling.

Indulging in reflections of this sort, the writer on going from his dinner that day to the anti-slavery office, to his surprise found an officer awaiting his coming.

Said officer was of the mayor’s police force. Before many moments had been allowed to pass, in which to conjecture his errand, the officer, evidently burdened with the importance of his mission, began to state his business substantially as follows:

“I have just received a telegraphic despatch from a slave-holder living in Maryland, informing me that six slaves had escaped from him, and that he had reason to believe that they were on their way to Philadelphia, and would come in the regular train direct from Harrisburg;

Furthermore I am requested to be at the depot on the arrival of the train to arrest the whole party, for whom a reward of $1300 is offered.

Now I am not the man for this business. I would have nothing to do with the contemptible work of arresting fugitives. I’d rather help them off. What I am telling you is confidential.

My object in coming to the office is simply to notify the Vigilance Committee so that they may be on the look-out for them at the depot this evening and get them out of danger as soon as possible. This is the way I feel about them; but I shall telegraph back that I will be on the look-out.”

While the officer was giving this information he was listened to most attentively, and every word he uttered was carefully weighed.

An air of truthfulness, however, was apparent; nevertheless he was a stranger and there was cause for great cautiousness.

[The committee deemed it prudent to hide the fugitives in separate accommodation in Philadelphia until the hunt died down. Then they could continue with their travels.]

Aftermath And Relief

[Charlotte and Harriet reached Western New York where they found work. Harriet was content to stay there but Charlotte headed for Canada and certain freedom.

Unfortunately, it appears that Charlotte wrote letters back to Baltimore that divulged too much detail about their escape. The letters implicated a railroad worker who had aided them.

I’ll let William Still pick up the narrative…]

On the strength of the information thus obtained, a well-known colored man, named Adams, was straightway arrested and put in prison at the instance of one of the owners, and also a suit was at the same time instituted against the Rail Road Company for damages—by which steps quite a huge excitement was created in Baltimore.

As to the colored man Adams, the prospect looked simply hopeless. Many hearts were sad in view of the doom which they feared would fall upon him for obeying a humane impulse (he had put the girls on the cars).

But with the Rail Road Company it was a different matter; they had money, power, friends, etc., and could defy the courts.

In the course of a few months, when the suit against Adams and the Rail Road Company came up, the Rail Road Company proved in court, in defense, that the prosecutor entered the cars in search of his runaway, and went and spoke to the two young women in “mourning” the day they escaped, looking expressly for the identical parties, for which he was seeking damages before the court, and that he declared to the conductor, on leaving the cars, that the said “two girls in mourning, were not the ones he was looking after,” or in other words, that “neither” belonged to him.

This positive testimony satisfied the jury, and the Rail Road Company and poor James Adams escaped by the verdict not guilty.

The owner of the lost property had the costs to pay of course, but whether he was made a wiser or better man by the operation was never ascertained.